NBS Technical Author, Roland Finch, sheds light on changes to classification and rules of measurement. Are we heading for coordination or conflict?

Introduction

In the construction industry, Collaboration is the key. Over a period of time, a number of reports have been issued, most notably by Egan and Latham, Task Forces and Working Groups set up, while many pages have been written on the subject. For over 25 years, successive Governments have been seeking to reduce construction costs by an elusive '20 %'. In doing this, a variety of means have been employed and proposed, the most recent of which is Building Information Modelling (BIM). One thing which has been consistent throughout this time, however, has been the 'Common Arrangement of Work Sections' classification (CAWS).

CAWS is maintained by the Construction Project Information Committee (CPIC) - a 'pan industry' body which is sponsored by and provides representation to the major industry institutions - including Architects, Surveyors, Engineers, Clients and Contractors organizations. Its purpose is to promote and support collaborative information exchange in our industry. CPIC developed CAWS in response to Government research on quality of building, which established that the quality of information passed from design office to site was a key factor in the quality of the final outcome. At the time, the commonly used library classification, CISfb - a system which developed from 'Construction Industry' and the Swedish 'Samarbetskomitten for Byggnadsfragor' (committee for building investigation), wasn't considered comprehensive enough for specification and pricing, particularly on the mechanical and electrical services side.

Some readers may not be conversant with CAWS, but they will be familiar with documents that follow its template, such as SMM7 and NBS, as well as many of the Architects' and Builders' price books - Spons, Laxtons and Wessex, for example. It has been recognized for some time that existing CAWS doesn't lend itself too well to computerized applications. For a start, the alphanumeric system is limited to 26 'top level' headings, (or 24 if you discount 'O' and 'I').

Uniclass

CAWS has been incorporated into another classification system - 'Uniclass', also developed by CPIC. Uniclass is the UK implementation of BS ISO 12006-2. This has fifteen tables but two which describe Work Sections; one for Building (J, which corresponds with CAWS) and one for Civil Engineering (K, which aligns to the Civil Engineering Standard Method of Measurement, CESMM).

Uniclass also has a table for Building Elements (G). CAWS is not ordered elementally, so is not appropriate for object naming in the software models. The software vendors, however, typically use Uniclass table G for this, but unfortunately there is not a simple link from table G to table J (CAWS).

CPIC decided some time ago that Uniclass had to change; this is explained in an article by Sarah Delany, CPIC secretary, which appeared on the NBS website in 2008: CPIC and Uniclass - who, what and why?

Current position

Having recognized the need for change, CPIC has instigated a consultation procedure on 'Uniclass 2' - which is proposed as the successor to Uniclass. There are a number of significant changes anticipated, most notably the change in emphasis to a 'work results' classification for the Architectural part of the work section table. These are explained in more detail on the CPIC website: www.cpic.org.uk/en/uniclass ![]()

At the same time, RICS (which is represented on CPIC) has been undertaking its own project to rationalize and simplify the rules of measurement for building works.

RICS has now launched two of the three volumes that comprise its 'New' Rules of Measurement (NRM). Volume 2 of NRM is due to supercede SMM7 with effect from 1 January 2013. As part of this work, NRM has developed its own indexing, which is a departure from both CAWS and Uniclass, and is intended to make it easier to map the document rules to other classification systems, thereby giving it more international appeal. At the same time, it has taken the opportunity of subdividing some sections for ease of use and greater clarity, so whereas SMM7 had 22 sections, NRM 2 has 41. It has also been aligned to the Standard Form of Cost Analysis, produced by BCIS.

'Classification' or 'Measurement' rules

It is important to recognize at this point that NRM is not a classification system in itself; it is a set of measurement rules, and one of the purposes of the new layout of NRM is that it is designed to map onto a variety of different classification systems, including CAWS and Uniclass.

The National Building Specification (NBS) is delivered through a number of specification products, each with slightly different formats. NBS is not a set of rules; it is an information template, commonly referred to as a Master Specification. However, each individual part of the specification is aligned directly to a classification system. Currently, most of the existing NBS specification templates are aligned to CAWS, but during 2011, a new product, NBS Create, was launched. This uses the proposed Uniclass 2 classification as its base.

So how do NBS and NRM relate? In many ways, the same as they always did. In moving away from CAWS, however, the RICS NRM has made it necessary to map between the two where other project documentation has been prepared in that format. For example, in general terms, Masonry, which was section 'F' in SMM7 is now section '14' in NRM 2.

Concrete work, however, which was previously measured in CAWS Group E, will now be in NRM 2 Section 11, 12 or 13 (in NRM, concrete work has been further subdivided into sections for 'in-situ', 'composite' and 'precast').

NRM anticipates that Bills of Quantities may now be codified in one of three ways:

1. 'Elemental', using the NRM 1 (BCIS SFCA) categories, e.g.

- Group element 0: Facilitating works.

- Group element 1: Substructure.

- Group element 2: Superstructure.

- Group element 3: Internal finishes.

- Etc.

2. Work sections, using the headings from NRM 2, e.g.

- 1. Preliminaries.

- 2. Off-site manufactured materials, components and buildings.

- 3. Demolitions.

- 4. Alterations, repairs and conservation 125.

- 5. Excavating and filling.

- Etc.

3. Package based, depending on the scope of work envisaged. e.g.

- Building No. 1.

- Building No. 2.

- Building No. 3.

- Building No. 4.

- Etc.

The measurement rules will be broadly the same in each case, however. For example, concrete work will still be measured in cubic metres, and brickwork will still be measured in square metres, with forming cavities and insulation included in the description. The major differences will occur when sourcing the specification that goes with that measurement. Because there is no classified specification information in NRM format, Bills of quantities will still need to refer to the old system; (CAWS/Uniclass), or, in due course the 'new' system; (Uniclass 2).

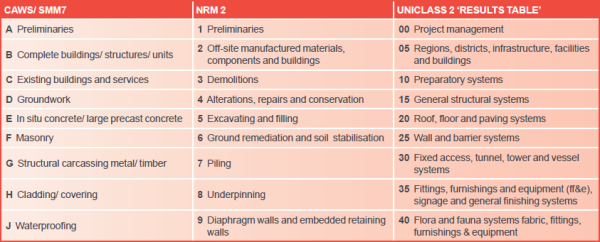

The example below is a comparison of some of the section headings used in CAWS, NRM 2 and Uniclass 2.

It can be seen that there are some notable differences in description and terminology, and there are also changes in scope. Some of these appear quite striking, but may only be due to terminology. In addition, it can be seen that the groupings are no longer in the same order in each classification - so there is no obvious direct mapping at this level. But in principle it is no different to the current system using SMM7, where work specified in one section may still be measured according to rules in other sections. For example, Site/ Street Furniture is measured under SMM7 using rules from Section N, but its properties are currently specified in CAWS section Q50.

In NRM 2, the same items would be measured in section 32, while Uniclass 2 requires them to be specified in section 35-35-30.

Summary

It is an often and well-repeated maxim that the one certainty is change. There are a number of drivers of this change and in this instance the main one is the need to support Building Information Modelling.

Some readers may recall the introduction of the Coordinated Project Information initiative which led to the formation of CPIC and the introduction of SMM7 in 1988. Others may recall that it took over 15 years to get to that point. Of course, differing classification systems is nothing new. Many architectural libraries still use CI/SfB - It has a number of commercial users, including RIBA Product Selector. So while no single classification is in common use, there is an ongoing task to link the various rules and systems. One advantage that we now have, of course, is the use of computer applications, which hopefully will make the process quicker.

The RIBA's research and innovation group, together with several industry partners, are developing tools to allow instant mapping and linkage between the various classifications, see www.bimgateway.co.uk ![]()

For end users it can be a bit of a chore to compare systems, and decide which one to use. The problem is that although there may be substantial areas of overlap, they are often designed for different purposes.

Conclusion

There's not quite a fight for global 'dominance' that we've seen in other areas of technology, VHS versus Betamax, or Microsoft Windows vs Apple Macintosh, or even Apple vs Samsung in the mobile phone arena, for example. Nevertheless, it can be seen that even those technologies can coexist, with plenty of designed applications to enhance and improve connections between them. Although change may be certain, it's also true that it takes time, not only to implement, but also to get used to.

Uniclass 2 is in the consultation stage, while RICS NRM is still being 'bedded in'. It's likely that there will be changes in both in the foreseeable future. It's also worth noting that the mobile phone industry - often held up as a leader of innovation - has taken nearly two decades just to agree on a common connector for chargers. It is the intention of all parties to improve significantly on that.