There are some events that we all remember, as if they are engraved in our minds: events so significant that we remember the dates that they occurred and where we were when we heard about them. The collapse of the Twin Towers, the death of Princess Diana and other shocking media newsflashes, events so often surrounded by tragedy.

The date is 15 April 1989, and I can still recall the walk up to Highbury stadium to watch Arsenal play, passing the street vendors selling scarves and badges from their Victorian terrace gardens which lined the approach to the North London ground. Standing next to my dad within the secure family enclosure, I remember looking across to the terraces on the other side of the pitch and watching the crowd swaying from side to side. Moments into the game, news spread down through the terraces of a tragedy unfolding 170 miles away in Sheffield. With people listening intently on portable radios, the mood distinctively changed to one of shock and disbelief as news filtered through the ground of a crowd crush at Hillsborough, during the FA Cup semi-final match between Liverpool and Nottingham Forest.

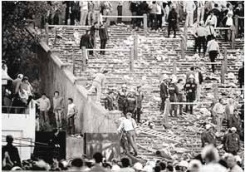

That afternoon, 94 people lost their lives, including my friend's father. The figure was eventually to rise to 96 lives. My dad no longer felt that it was safe to take me to football matches and the face of English football was to change forever. It was time for a thorough look at the safety surrounding football grounds.

Hillsborough, Photos: Sportszest

Previous incidents

In 1971, 66 people died at the Ibrox Stadium in Glasgow, following a crush as supporters left the stadium. Believing that Celtic had won, Rangers supporters were leaving the stadium early, only to turn back on stairway 13 following an equalising goal. A spectator slipping on the steps was all it took for a devastating crush to occur. Preventive measures were established in the formation of the Wheatley Committee, and the subsequent Safety of Sports Grounds Act 1975 and Guide to Safety at Sports Grounds detailed requirements and advice concerning safety measures at sports grounds. Although Building Regulations made reference to specific buildings, there was no governing statute about sports grounds in place until that point in time: accidents at sporting venues were dealt with on the basis of common law principles regarding occupiers and their visitors. The Safety of Sports Grounds Act 1975 applied to stadia that catered for 10,000 spectators or more and which were substantially surrounded by spectator accommodation. It introduced a system of safety certification for sports grounds by Local Authorities which remains substantially unchanged, with the Local Authority being required to determine the safe capacity of the ground. A Safety Certificate contains terms and conditions required by the legislation, typically stating the specific activities permitted at the sports ground, maximum capacities allowed and any other specific requirements to ensure public safety and compliance with national guidance and legislation.

A number of events highlighted serious safety failures in football stadia in the 1980s, including:

- A fire at Valley Parade stadium, Bradford, in 1985, resulting in 56 deaths when rubbish underneath an old wooden stand caught alight.

- Fighting between English and Italian fans at the Heysel Stadium in Brussels just weeks later, leading to 39 fatalities.

The subsequent Popplewell Inquiry and report considered the Safety of Sports Ground Act 1975, which at that time was considered to be limited in football grounds. The Act was reissued in 1987; its scope was extended to include sports grounds as a general term and the previous distinction between a stadium and a sports ground was abolished. The report also initiated the Fire Safety and Safety of Places of Sports Act 1987, which included requirements for stands that provide covered accommodation for 500 or more spectators in sports grounds. Furthermore, wooden stands were condemned and additional fire exits required. Yet many grounds still had touchline perimeter fencing to restrict pitch invasions, commonplace in the '70s. Thankfully these were not in place at Bradford: they would have likely lead to more deaths as people would have been prevented from gaining a safe retreat onto the pitch. To assist football clubs with the huge costs of implementing the Safety of Sports Ground Act, the Government set up the Football Grounds Improvement Trust, later to become the Football Trust, which was wound up in 2000 to be replaced by the Football Foundation.

UK stadia - a historical perspective

Football is our national game. The British were the first to export it to the world, and consequently, at the time of these incidents, many of our stadia were old and tired. They had been developed in an ad hoc fashion on cramped sites, often within built-up residential areas (unlike our European counterparts, who often benefitted from planned, spacious sites with modern conditions). Stadia in the UK were usually owned by a particular football club rather than a consortium, and were generally used for the sole purpose of football. With no space for an athletic track around the periphery of the pitch or other fee-generating activities, pressure to generate revenue meant that standing terraces were an effective method of packing in a capacity crowd, with supporters typically preferring to watch the match close to touchlines.

Following Hillsborough

In 1990, addressing the Heysel disaster and Bradford fire, the Government introduced the Football Spectators Act 1989. This Act initiated the Football Licensing Authority (FLA) (which became the Sports Grounds Safety Authority in 2011) which, in an effort to combat football hooliganism, implemented the Football Membership Scheme: the compulsory distribution of identity cards to every football fan attending league, cup and international matches played in England and Wales. Despite government backing, only 13 of the 92 English league clubs actually implemented the use of identity cards by the initial deadline date and the scheme was soon abandoned. In the aftermath of the Hillsborough disaster, Lord Justice Taylor was appointed by the Home Office to enquire into the events of the tragedy and make recommendations about the needs of crowd control and safety at sports events. The report made 76 recommendations when it was published in 1990. A pivotal recommendation was for top division clubs in England and Scotland to move away from standing towards all-seated stadia, with further recommendations made on perimeter fences, crash barriers and police planning (including provision of a police control room).

By 1994, all English Premier League club stadia were all-seated. With the lure of commercial deals, TV viewing rights and merchandising opportunities, clubs were now starting to view the stadium as an income generator, and pressure grew to develop bigger and better facilities to accommodate the increase in spectators' expectations. However, simply retrofitting seats to a terrace is not a straightforward process, often requiring the profile of the terrace to be substantially altered. As many of the existing grounds were within residential built-up areas and required land acquisition, relocation was the only viable solution for many.

One of the recommendations set out in the Taylor report was for a review of the Home Office guide, Safety at Sports Grounds. Unlike previous disasters such as Heysel, Hillsborough was not a result of fighting or violence: it was down to congestion and overcrowding following a series of mismanaged events. The Guide to Safety at Sports Grounds (also known as the Green Guide) is currently in its fifth edition and gives detailed advice on safety measures needed at new and existing sports grounds, and measures to improve safety both in terms of their design and safety management. The guidance relates to entrances and exits, structure, stands and buildings, stairways and ramps, terraces, crash barriers and handrails, and perimeter walls and fences, and also focuses on management responsibility.

Seating

The introduction of seating wasn't a recommendation that went down well with all fans, particularly those who thought that their identity would be lost. However, Taylor recognized that while there is no one solution which will achieve total safety and cure all problems of behaviour and crowd control, seating does more to achieve these objectives than any other measure. A seat, not only more comfortable than standing for a full 90 minutes of play, also provides the spectator with territorial space and a zone of protection. It also serves as an important and strategic safety measure in that there can only be one valid ticket per allocated seat, and troublemakers can easier be identified through the assistance of CCTV.

The Green Guide recommends that the safe capacity of seated areas does not automatically correspond to the number of actual seats provided: the capacity should instead be set at a number which the stewards can safely manage. The Guide also provides assessment for seated accommodation using the (P) and (S) factors which should be reassessed annually or when physical alterations to the ground, safety management structure or personnel have taken place. In order to establish the capacity of people that can be safely accommodated in a section, each part of the ground's viewing accommodation should be assessed according to its physical condition (known as the P factor), as well as according to the quality of the safety management of the area (known as the S factor) by applying a numerical value that can be quantified, usually between 0.0 and 1.0.

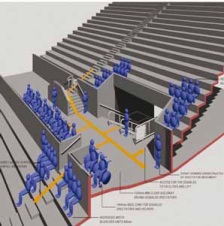

Model simulation. Swansea Liberty Stadium, TTH Architects

Further guidance on sightlines, as well as on seat width and depths, can be found in BS EN 13200-1:2003 Spectator facilities. Layout criteria for spectator viewing area. Specification' and Sports grounds and stadia guide no.1. Accessible Stadia. While we can begin to improve safety while people are seated, the spectator faces greatest danger when entering, exiting and circulating the ground. Therefore, attention should also be given to both the Model simulation. Swansea Liberty Stadium, TTH Architects concourse (which acts as a circulation system) and the vomitory (an access route built into the gradient of the stand which links the spectator accommodation to the concourse).

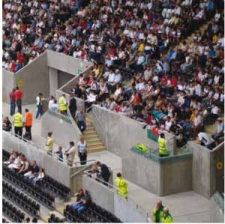

Exits and seating. Blackpool FC, Bloomfield Road Stadium, TTH Architects

Management

The Green Guide places great emphasis on responsibility for the safety of spectators at sports grounds, which rests at all times with the ground management. Clear, efficient and reliable communications are an integral part of any safety management operation; therefore, a coordinated approach between representatives of the Local Authority, police, fire, ambulance and ground management is required. Under the Safety of Sports Grounds Act 1975, which brought about the introduction of the safety certificate, the Local Authority is responsible for both issuing and enforcing a safety certificate in respect of sports grounds designated by the Secretary of State. The Act defines a sports ground as a place where sports or other competitive activities take place in the open air, and where accommodation has been provided for spectators. Currently these comprise grounds with accommodation for over 10,000 spectators where sports are played, and grounds occupied by Football Association (FA) Premier and Football League clubs with accommodation for over 5,000 spectators. (What the 1975 Act didn't foresee was that a sports ground might be fitted with a roof that could be closed for certain events). For grounds with stands that have the capacity to accommodate at least 500 spectators undercover and which are not designated under the 1975 Act, Part 3 of the Fire Safety and Safety of Places of Sport Act 1987 provides for certification by Local Authorities.

Effective safety management also requires the employment, hire or contracting of stewards to assist with the circulation of spectators, prevent overcrowding and reduce the likelihood and incidence of disorder. Building on the advice of Lord Taylor and the police, the Green Guide recommends that a central control point should form the hub of the safety management's communications network. Expanding on this guidance, The Sports Grounds Safety Authority (SGSA), which superseded the Football Licensing Authority, publishes Control Rooms. This provides details of relevant BSs and BS ENs for CCTV and public address systems, and contains detailed advice on identifying the optimum location for the control room. Further Guidance notes on CCTV can be found in Guidance notes for the procurement of CCTV for public safety at football grounds 2nd edition. While CCTV has become an integral part of the stadium safety strategy, a CCTV system should never be considered as a substitute for good stewarding or other forms of safety management.

Conclusion

Today's stadia developments are not only constrained by financial factors: legislation and local planning issues are increasingly important. The modern stadium has developed to include commercial and community needs, incorporating hotels, residences, leisure and retail. In the years that have followed Hillsborough, we have seen vast improvements in safety and spectator management. As football becomes increasingly more international, further safety regulations have to be followed. Technical guidance is provided by FIFA and UEFA. A safe environment can be created with the use of modern communication systems, surveillance and seating; however, these will not compensate for poor crowd management. Football clubs are big businesses underpinned by large commercial endorsements and advertising rights. The game today is a far cry from the standing terraces, and thankfully we have not seen a repeat in English football of the scenes that took place on that fateful afternoon of 15 April1989: a date which will forever be engrained in my memory.