Europe is now host to the greatest regional concentration of government-led BIM programmes in the world. Finland and Norway were first to set standards, followed by procurement policies from the UK, Netherlands and Italy; and most recently joint government and industry initiatives from France, Germany and Spain. Europe’s central policy and governance function, the European Commission, endorsed BIM as an enabler for delivering public works by encouraging its use in the EU Public Procurement Directive (2014).

The newly-formed EU BIM Task Group is co-funded by the European Commission to bring together these national initiatives into a common and aligned European approach to develop a world-class digital construction sector.

This unusual public collaboration raises several questions: why are governments and public sector organisations taking a leadership role to encourage BIM and, more broadly, the digitalisation of industry? What is the value proposition for collaboration and alignment across European member states? And how might this alignment affect the European construction sector and global markets? Before looking at governments’ interest in BIM, what does BIM mean to public authorities? Building Information Modelling (BIM) can be thought of as ‘digital construction’. It combines the use of 3D computer modelling with asset and project information to improve collaboration, coordination and decision making when delivering and operating public assets. It is a technology-based approach to construction that makes the complex understandable, and outcomes more predictable.

Why are governments encouraging BIM?

Three trends are focusing public sector minds on finding new ways of working. Firstly, governments and public agencies across Europe are adapting to the new norm of increased pressure on public spending. This is being driven by macro issues such as bearing the cost of an ageing population, rising social welfare and national debt concerns. These issues are far from unique – governments around the world are facing similarly tough budgetary constraints.

Secondly, despite the fiscal challenges, governments still need to build and fund national infrastructure for the future. Putting infrastructure development on hold harms the future prospects of a region or country as inadequate infrastructure limits prospects for growth or inward investment. Clearly, the ‘do nothing’ option for governments is not an attractive one.

Thirdly, to compound the public challenge, increasing regulation and policy drivers to reduce consumption of natural resources, including fossil fuels, are creating an acute need for public procurers to find new ways to address this three-sided conundrum: spend carefully, build more, and build to a higher, more sustainable quality standard.

The construction sector holds the promise of a significant contribution to all of these three challenges.

The sector represents a significant slice of budgets under scrutiny; therefore it is of interest to government agencies to extract greater value. Also, the built environment is widely recognised to be one of the largest consumers of natural resources and producers of carbon emissions. It accounts for approximately 40% of the world annual resource consumption, and emits approximately the same proportion of carbon.

The sector rightly has a self-interest to maintain and attract capital flows of investment from the public and private sector to continue with public infrastructure plans; therefore it is motivated to help solve the challenges of ‘build more for the same or less' and to sustainable standards.

In addition to the clear opportunity the sector holds to address public drivers, it is burdened with stubbornly low (and falling) productivity rates and high wastage. The UK’s National Audit Office (*Modernising Construction [2001]) estimates that 30% of construction costs are wasted in unproductive activities. This figure is evident in the global construction market – it is not a solely UK or European problem.

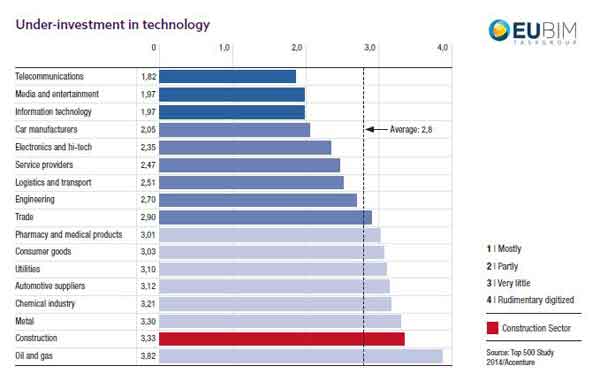

The Economist (in its report ‘Rethinking productivity across the construction industry’) lays part of the blame for this low productivity on poor coordination between the sector’s many and fragmented stakeholders. Inadequate information management is also identified as a root cause of the sector’s unsustainable performance.Accenture’s 2014 Top 500 Study places construction at the bottom of the league table for investing in and adopting technology. This lowly position is in stark contrast to technology take-up in other traditionally labour-intensive sectors such as manufacturing, retail and aerospace, where productivity rates have climbed.

The message is clear: the convergence of ‘digital’ with construction holds the promise of getting more from reduced budgets by increased productivity and getting a more sustainable built environment. BIM provides greater clarity and certainty of project delivery, thus helping to minimise cost overruns and improve timely delivery of public projects, helping to address the squeeze on public budgets.

As a decision support system, BIM can act as a powerful tool to address sustainability challenges; it helps to optimise energy and resource efficiency; and can perform an enabling role in the evolving circular economy agenda. These are key sustainability policies for Europe’s governments and public procurers.

Given the value of BIM to the public agenda and the sector’s systemic under-investment in technology, it is little surprise that governments take the view that the sector is well overdue an upgrade. Governments are recognising that policy and public procurement can act as a catalyst for this digital transition in a fragmented and diverse sector.

Why are public agencies collaborating?

In the past four years a surge of government-led BIM and digital programmes have launched across Europe. The argument on whether governments can benefit from BIM and help lead the sector’s digital transition appears well and truly answered: it does benefit and it can lead.

With multiple countries initiating digital programmes, the possibility of nationalism and with it protectionism through proprietary national approaches is raised. This scenario could lead to competition barriers across the European Single Market. Would we want to see a French, Spanish, German or UK engineer have to re-skill, re-tool and re-invest in a bid to work across borders complying with member state specific ‘BIM requirements’?

Governments want to increase productivity and reduce the costs of the construction sector – not to add a cost burden of compliance to country-specific methods. What are the benefits of cross-border collaboration? On the positive, a pooling of intellectual horsepower and normalising of common practices can reduce individual member state costs for developing digitalisation policies and strategies. Hence, learning from each other will reduce waste and accelerate digitalisation and increase shared benefits.

Collaboration also makes for more robust and proven programmes, which in turn increases the likelihood of implementing successful and impactful policies. Furthermore, adoption levels within member states are likely to be greater when a regional ‘competitive’ effect operates. For example, an engineer, architect or contractor will not want to fall behind the capability level of a neighbouring ‘BIM ready’ country. In this case, if a unified BIM policy is introduced, it would be more likely that the supply chain would be inclined to invest and re-skill than if it were a different type of approach.

To make this vision of a common approach for BIM a reality, the EU BIM Task Group is bringing together national initiatives to an aligned and common approach for the use of BIM in Europe’s public works. The group is comprised of public clients and policy makers and nominated industry advisers.

The vision of the group is to increase the value for public money on the delivery and operation of public assets to improve whole-life cycle performance of public assets and to foster a world-class digital, open and competitive construction sector.

The group is co-funded by the European Commission (EC) for two years (2016-2017) to deliver on its promise of a common European approach. The EC is in support of its vision as part of a wider ambition to improve competitiveness of the construction sector, especially SMEs, and related policy actions to digitalise the sector.

The Task Group aims to normalise the use and specification of BIM by European public clients and policy makers to deliver shared benefits for Europe’s public realm and construction sector. To achieve this it will develop a handbook describing the common practices and principles for ‘European BIM’.

This may lead to a minimum performance level for BIM across many European states.The handbook will describe common practices and principles for three areas:

- Procurement procedures for tendering and contracting

- Technical considerations for the collection, processing and use of information

- Skills and role development principles

The task group has a programme for collating and identifying best practice and performance criteria. It will engage with public clients across Europe to spread its message, and will be consulting with standards bodies and industry.

The EU BIM Task Group held its first official steering committee meeting in Brussels on 19 January 2016. At its Launch Reception on 29 February, attended by Brussels-based European construction sector and product associations, the group announced its aspiration to grow a digital single market for construction and to build a world-class sector on the world stage. How might this affect the future of the European industry and international markets?

How will this unified 'EU BIM' affect the future of the industry?

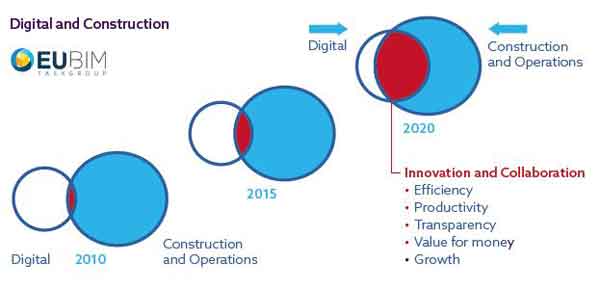

Assuming that ‘EU BIM’ national digital programmes continue to increase and normalise BIM adoption across Europe, it would be reasonable to expect that the industry will move up Accenture’s league table of digital adoption. Given that a number of national programmes are stating a target between 2016 and 2020, within five years we can expect a significant proportion of the European industry to move from digitally naïve to ‘digital natives’.

But digital is a means to a goal and not the end itself. The benefit to the public community will be higher productivity, resulting in greater output for the same spend; higher-quality public assets leading to social and environment goods being delivered, such as improved social outcomes from hospitals, schools and infrastructure; and more sustainable choices on operating energy demands and carbon cost. Addressing the European three-sided problem of squeezed budgets, the need for public infrastructure and sustainable decisions is the prize for the public sector ‘built environment’.

Within five years we can expect a significant proportion of the European industry to move from digitally naïve to ‘digital natives’.

This increasing digital convergence (see diagram above) will present opportunities and threats for the private sector. As seen already in early adopter countries, Europe-wide competition for digitally skilled professionals is likely to increase. A competition to up-skill and develop new services will be difficult for some while others forge ahead in an inevitably messy and unpredictable free-market process.

Getting the other side of this transition offers the prospect of a modern 21st century industry attracting fresh talent from the tech and manufacturing sectors.

A European centre of excellence in digital construction will inevitably permeate to international markets – as already seen in the Middle East and Asia, where clients are demanding digital deliverables as standard in contracts.

Digital is set to become the global lingua franca for designing, building and operating the world’s built environment. This will create new opportunities for growth from the global export market, which is forecast to outstrip the European domestic market performance over the next decade. BIM has become a proxy for digital information exchange and better ways of working; it looks set to augur in a new world order of digital construction based on who can mine and use information to the greatest effect.

By working towards a unified European approach for digital construction we can grow the size of the sector and position Europe to compete and win in the global market.